Table Of Contents

- 6. Models and Databases

Previous topic

Next topic

7. Models, Templates and Views

This Page

Quick search

Enter search terms or a module, class or function name.

Note

A newer version of this tutorial using Django 1.9 is available from Leanpub: https://leanpub.com/tangowithdjango19

Working with databases often requires you to get your hands dirty messing about with SQL. In Django, a lot of this hassle is taken care of for you by Django’s object relational mapping (ORM) functions, and how Django encapsulates databases tables through models. Essentially, a model is a Python object that describes your data model/table. Instead of directly working on the database table via SQL, all you have to do is manipulate the corresponding Python object. In this chapter, we’ll walkthrough how to setup a database and the models required for Rango.

First, let’s go over the data requirements for Rango. The following list provides the key details of Rango’s data requirements.

Before we can create any models, the database configuration needs to be setup. In Django 1.7, when you create a project, Django automatically populates the dictionary called DATABASES, which is located in your settings.py. It will contain something like:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3',

'NAME': os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'db.sqlite3'),

}

}

As you can see the default engine will be a SQLite3 backend. This provides us with access to the lightweight python database, SQLite, which is great for development purposes. The only other value we need to set is the NAME key/value pair, which we have set to DATABASE_PATH. For other database engines, other keys like USER, PASSWORD, HOST and PORT can also be added to the dictionary.

Note

While using an SQLite engine for this tutorial is fine, it may not perhaps be the best option when it comes to deploying your application. Instead, it may be better to use a more robust and scalable database engine. Django comes with out of the box support for several other popular database engines, such as PostgreSQL and MySQL. See the official Django documentation on Database Engines for more details. You can also check out this excellent article on the SQLite website which explains situation where you should and you shouldn’t consider using the lightweight SQLite engine.

With your database configured in settings.py, let’s create the two initial data models for the Rango application.

In rango/models.py, we will define two classes - both of which must inherit from django.db.models.Model. The two Python classes will be the definitions for models representing categories and pages. Define the Category and Page models as follows.

class Category(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=128, unique=True)

def __unicode__(self): #For Python 2, use __str__ on Python 3

return self.name

class Page(models.Model):

category = models.ForeignKey(Category)

title = models.CharField(max_length=128)

url = models.URLField()

views = models.IntegerField(default=0)

def __unicode__(self): #For Python 2, use __str__ on Python 3

return self.title

When you define a model, you need to specify the list of attributes and their associated types along with any optional parameters. Django provides a number of built-in fields. Some of the most commonly used are listed below.

Check out the Django documentation on model fields for a full listing.

For each field, you can specify the unique attribute. If set to True, only one instance of a particular value in that field may exist throughout the entire database model. For example, take a look at our Category model defined above. The field name has been set to unique - thus every category name must be unique.

This is useful if you wish to use a particular field as an additional database key. You can also specify additional attributes for each field such as specifying a default value (default='value'), and whether the value for a field can be NULL (null=True) or not.

Django also provides simple mechanisms that allows us to relate models/database tables together. These mechanisms are encapsulated in three further field types, and are listed below.

From our model examples above, the field category in model Page is of type ForeignKey. This allows us to create a one-to-many relationship with model/table Category, which is specified as an argument to the field’s constructor. You should be aware that Django creates an ID field for you automatically in each table relating to a model. You therefore do not need to explicitly define a primary key for each model - it’s done for you!

Note

When creating a Django model, it’s good practice to make sure you include the __unicode__() method - a method almost identical to the __str__() method. If you’re unfamiliar with both of these, think of them as methods analogous to the toString() method in a Java class. The __unicode__() method is therefore used to provide a unicode representation of a model instance. Our Category model for example returns the name of the category in the __unicode__() method - something which will be incredibly handy to you when you begin to use the Django admin interface later on in this chapter.

Including a __unicode__() method in your classes is also useful when debugging your code. Issuing a print on a Category model instance without a __unicode__() method will return <Category: Category object>. We know it’s a category, but which one? Including __unicode__() would then return <Category: python>, where python is the name of a given category. Much better!

With our models defined, we can now let Django work its magic and create the table representations in our database. In previous versions of Django this would be performed using the command:

$ python manage.py syncdb

However, Django 1.7 provides a migration tool to setup and update the database to reflect changes in the models. So the process has become a little more complicated - but the idea is that if you make changes to the models, you will be able to update the database without having to delete it.

If you have not done so already you first need to initial the database. This is done via the migrate command.

$ python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, contenttypes, auth, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying contenttypes.0001_initial... OK

Applying auth.0001_initial... OK

Applying admin.0001_initial... OK

Applying sessions.0001_initial... OK

If you remember in settings.py there was a list of INSTALLED_APPS, this initial call to migrate, creates the tables for the associated apps, i.e. auth, admin, etc. There should be a file called, db.sqlite in your project base directory.

Now you will want to create a superuser to manage the database. Run the following command.

$ python manage.py createsuperuser

The superuser account will be used to access the Django admin interface later on in this tutorial. Enter a username for the account, e-mail address and provide a password when prompted. Once completed, the script should finish successfully. Make sure you take a note of the username and password for your superuser account.

Whenever you make changes to the models, then you need to register the changes, via the makemigrations command for the particular app. So for rango, we need to issue:

$ python manage.py makemigrations rango

Migrations for 'rango':

0001_initial.py:

- Create model Category

- Create model Page

If you inspect the rango/migrations folder, you will see that a python script have been created, called, 0001_initial.py''. To see the SQL that will be performed to make this migration, you can issue the command, ``python manage.py sqlmigrate <app_name> <migration_no>. The migration number is show above as 0001, so we would issue the command, python manage.py sqlmigrate rango 0001 for rango to see the SQL. Try it out.

Now, to apply these migrations (which will essentially create the database tables), then you need to issue:

$ python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, rango, contenttypes, auth, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying rango.0001_initial... OK

Warning

Whenever you add to existing models, you will have to repeat this process running python manage.py makemigrations <app_name>, and then python manage.py migrate

You may have also noticed that our Category model is currently lacking some fields that we defined in Rango’s requirements. We will add these in later to remind you of the updating process.

Before we turn our attention to demonstrating the Django admin interface, it’s worth noting that you can interact with Django models from the Django shell - a very useful aid for debugging purposes. We’ll demonstrate how to create a Category instance using this method.

To access the shell, we need to call manage.py from within your Django project’s root directory once more. Run the following command.

$ python manage.py shell

This will start an instance of the Python interpreter and load in your project’s settings for you. You can then interact with the models. The following terminal session demonstrates this functionality. Check out the inline commentary to see what each command does.

# Import the Category model from the Rango application

>>> from rango.models import Category

# Show all the current categories

>>> print Category.objects.all()

[] # Returns an empty list (no categories have been defined!)

# Create a new category object, and save it to the database.

>>> c = Category(name="Test")

>>> c.save()

# Now list all the category objects stored once more.

>>> print Category.objects.all()

[<Category: test>] # We now have a category called 'test' saved in the database!

# Quit the Django shell.

>>> quit()

In the example, we first import the model that we want to manipulate. We then print out all the existing categories, of which there are none because our table is empty. Then we create and save a Category, before printing out all the categories again. This second print should then show the Category just added.

Note

The example we provide above is only a very basic taster on database related activities you can perform in the Django shell. If you have not done so already, it is good time to complete part one of the official Django Tutorial to learn more about interacting with the models. Also check out the official Django documentation on the list of available commands for working with models.

One of the stand-out features of Django is that it provides a built in, web-based administrative interface that allows us to browse and edit data stored within our models and corresponding database tables. In the settings.py file, you will notice that one of the pre-installed apps is django.contrib.admin, and in your project’s urls.py there is a urlpattern that matches admin/.

Start the development server:

$ python manage.py runserver

and visit the url, http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/. You should be able to log into the Django Admin interface using the username and password created for the superuser. The admin interface only contains tables relevant to the sites adminstration, Groups and Users. So we will need to instruct Django to also include the models from rango.

To do this, open the file rango/admin.py and add the following code:

from django.contrib import admin

from rango.models import Category, Page

admin.site.register(Category)

admin.site.register(Page)

This will register the models with the admin interface. If we were to have another model, it would be a trivial case of calling the admin.site.register() function, passing the model in as a parameter.

With all of these changes made, re-visit/refresh: http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/. You should now be able to see the Category and Page models, like in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Django admin interface. Note the Rango category, and the two models contained within.

Try clicking the Categorys link within the Rango section. From here, you should see the test category that we created via the Django shell. Try deleting the category as we’ll be populating the database with a population script next. The interface is easy to use. Spend a few minutes creating, modifying and deleting both categories and pages. You can also add new users who can login to the Django admin interface for your project by adding a user to the User in the Auth application.

Note

Note the typo within the admin interface (categorys, not categories). This problem can be fixed by adding a nested Meta class into your model definitions with the verbose_name_plural attribute. Check out Django’s official documentation on models for more information.

Note

The example admin.py file for our Rango application is the most simple, functional example available. There are many different features which you can use in the admin.py to perform all sorts of cool customisations, such as changing the way models appear in the admin interface. For this tutorial, we’ll stick with the bare-bones admin interface, but you can check out the official Django documentation on the admin interface for more information if you’re interested.

Entering test data into your database tends to be a hassle. Many developers will add in some bogus test data by randomly hitting keys like they are a monkey trying to write Shakespeare. If you are in a small development team, then everyone has to enter in some data. Rather than do this independently, it is better to write a script so that everyone has similar data, and so that everyone has useful and appropriate data, rather than junk test data. So it is good practice to create what we call a population script for your database. This script is designed to automatically populate your database with test data for you.

To create a population script for Rango’s database, we start by creating a new Python module within our Django project’s root directory (e.g. <workspace>/tango_with_django_project/). Create the populate_rango.py file and add the following code.

import os

os.environ.setdefault('DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE', 'tango_with_django_project.settings')

import django

django.setup()

from rango.models import Category, Page

def populate():

python_cat = add_cat('Python')

add_page(cat=python_cat,

title="Official Python Tutorial",

url="http://docs.python.org/2/tutorial/")

add_page(cat=python_cat,

title="How to Think like a Computer Scientist",

url="http://www.greenteapress.com/thinkpython/")

add_page(cat=python_cat,

title="Learn Python in 10 Minutes",

url="http://www.korokithakis.net/tutorials/python/")

django_cat = add_cat("Django")

add_page(cat=django_cat,

title="Official Django Tutorial",

url="https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.5/intro/tutorial01/")

add_page(cat=django_cat,

title="Django Rocks",

url="http://www.djangorocks.com/")

add_page(cat=django_cat,

title="How to Tango with Django",

url="http://www.tangowithdjango.com/")

frame_cat = add_cat("Other Frameworks")

add_page(cat=frame_cat,

title="Bottle",

url="http://bottlepy.org/docs/dev/")

add_page(cat=frame_cat,

title="Flask",

url="http://flask.pocoo.org")

# Print out what we have added to the user.

for c in Category.objects.all():

for p in Page.objects.filter(category=c):

print "- {0} - {1}".format(str(c), str(p))

def add_page(cat, title, url, views=0):

p = Page.objects.get_or_create(category=cat, title=title)[0]

p.url=url

p.views=views

p.save()

return p

def add_cat(name):

c = Category.objects.get_or_create(name=name)[0]

return c

# Start execution here!

if __name__ == '__main__':

print "Starting Rango population script..."

populate()

While this looks like a lot of code, what it does is relatively simple. As we define a series of functions at the top of the file, code execution begins towards the bottom - look for the line if __name__ == '__main__'. We call the populate() function.

Warning

When importing Django models, make sure you have imported your project’s settings by importing django and setting the environment variable DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE to be the project setting file. Then you can call django.setup() to import the django settings. If you don’t, an exception will be raised. This is why we import Category and Page after the settings have been loaded.

The populate() function is responsible for the calling the add_cat() and add_page() functions, who are in turn responsible for the creation of new categories and pages respectively. populate() keeps tabs on category references for us as we create each individual Page model instance and store them within our database. Finally, we loop through our Category and Page models to print to the user all the Page instances and their corresponding categories.

Note

We make use of the convenience get_or_create() method for creating model instances. As we don’t want to create duplicates of the same entry, we can use get_or_create() to check if the entry exists in the database for us. If it doesn’t exist, the method creates it. This can remove a lot of repetitive code for us - rather than doing this laborious check ourselves, we can make use of code that does exactly this for us. As we mentioned previously, why reinvent the wheel if it’s already there?

The get_or_create() method returns a tuple of (object, created). The first element object is a reference to the model instance that the get_or_create() method creates if the database entry was not found. The entry is created using the parameters you pass to the method - just like category, title, url and views in the example above. If the entry already exists in the database, the method simply returns the model instance corresponding to the entry. created is a boolean value; true is returned if get_or_create() had to create a model instance.

The [0] at the end of our call to the method to retrieve the object portion of the tuple returned from get_or_create(). Like most other programming language data structures, Python tuples use zero-based numbering.

You can check out the official Django documentation for more information on the handy get_or_create() method.

When saved, we can run the script by changing the current working directory in a terminal to our Django project’s root and executing the module with the command $ python populate_rango.py. You should then see output similar to that shown below.

$ python populate_rango.py

Starting Rango population script...

- Python - Official Python Tutorial

- Python - How to Think like a Computer Scientist

- Python - Learn Python in 10 Minutes

- Django - Official Django Tutorial

- Django - Django Rocks

- Django - How to Tango with Django

- Other Frameworks - Bottle

- Other Frameworks - Flask

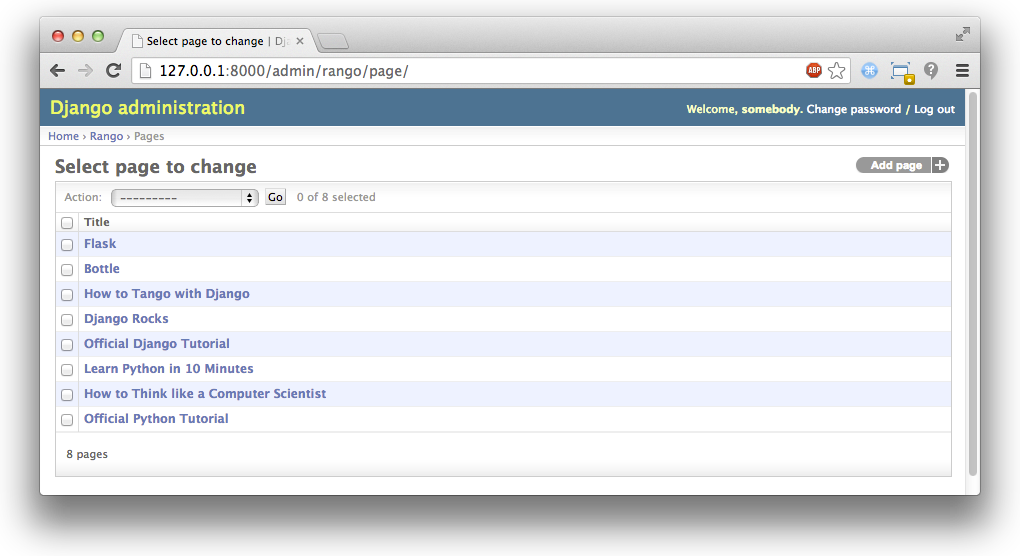

Now let’s verify that the population script populated the database. Restart the Django development server, navigate to the admin interface, and check that you have some new categories and pages. Do you see all the pages if you click Pages, like in Figure 3?

Figure 3: The Django admin interface, showing the Page table populated with sample data from our population script.

A population script takes a little bit of time to write but when you are working with a team, you will be able to share the population script so that everyone can create the database and have it populated. Also, for unit testing it will come in handy.

Now that we’ve covered the core principles of dealing with Django’s models functionality, now is a good time to summarise the processes involved in setting everything up. We’ve split the core tasks into separate sections for you.

With a new Django project, you should first tell Django about the database you intend to use (i.e. configure DATABASES in settings.py). You can also register any models in the admin.py file to make them accessible via the admin interface.

The workflow for adding models can be broken down into five steps.

Invariably there will be times when you will have to delete your database. In which case you will have to run the migrate command, then createsuperuser command, followed by the sqlmigrate commands for each app, then you can populate the database.

Now that you’ve completed the chapter, try out these exercises to reinforce and practice what you have learnt.

If you require some help or inspiration to get these exercises done, these hints will hopefully help you out.

Figure 4: The updated admin interface page view, complete with columns for category and URL.